CARL GROSE, WRITER

HACKING A PATH THROUGH THE BLACK FOREST: ADAPTING THE TIN DRUM

Mike, Charles and I were looking to do something as a follow up to Dead Dog in a Suitcase (and other love songs) and The Tin Drum fell out of my mouth. At the time, I had only seen the film many years ago. But the image of Oskar (played by David Bennett in Volkar Schlondorff’s film) had always stayed with me. With his red and white drum, and his weird, too-wide-eyed scream, he was both a disturbing, funny and arresting image. A strange child in protest against the world.

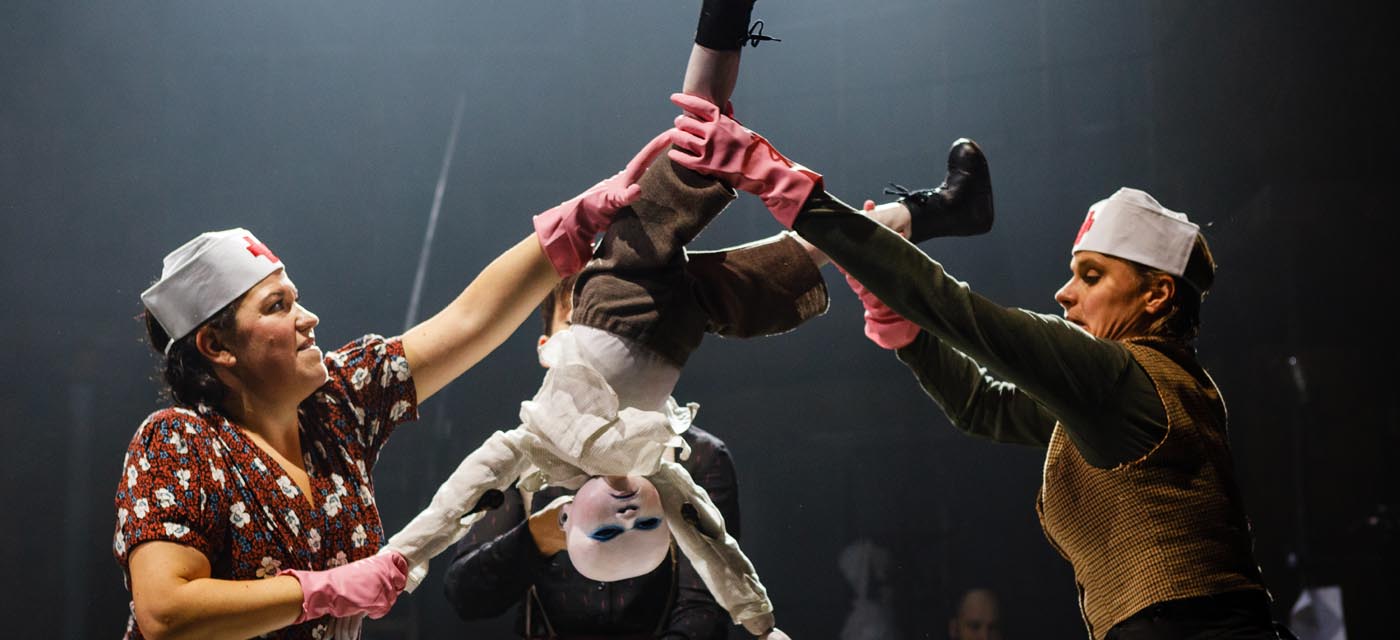

I read the book. Which was extraordinary. On one level, a complex literary trick, on another, a surreal autobiography, a terrifying historical document, and a bizarre folk tale. It was also 500 pages long. This sprawling picaresque, narrated by Oskar as a 30 year old man as an inmate in an asylum, wildly ricochets off in any given direction at any given moment. Oskar was also that very literary of protagonists – the unreliable narrator. Fine in a book. Harder to put on stage.

But I loved it. Its characters, its world, and the fact that passages of the book (published in 1959) read like today’s news – the rise of the far right in Europe, the displacement of people, questions of ethnicity and identity.

But to find a workable structure, some radical choices had to be made. If I was to hack my way through this glorious black forest of a novel, I needed to find a simple thread to lead me through it. I decided to let it present itself to me when it was ready.

I was in my kitchen washing up with my son (aged three at the time) when I heard Bowie had died. Though I could never claim to be a huge fan, I was still floored by the news. One of the great culture-heroes of our time had gone. Bowie changed the world. He challenged the status quo and he drew people together and allowed them to be themselves. He was alien. Odd. Alluring. He shattered things into fragments and put them back together again. Like Oskar. Oskar the vivid outsider. Oskar the trickster. Oskar the alien. Wham bam thank you, ma’am.

Grass’s novel is riven with references to classical stories, myths and folklore. And so this was how the world of the show felt it should be. A folk tale, of sorts. And Oskar, now part Bowie, part my son Arthur, became a strange kind of classical hero. A mischievous subversion of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. Oskar was Odysseus gone wrong. A loud-mouth punk here to save the world from conformity and hypocrisy.

This subversion of all things classical also gave me the idea to explore the notion of the epic poem. Doing a straight adaptation of this book was not of any interest to us. And if you’re working with Charles Hazlewood, music is going to be a key form of the storytelling. And so, I started to think of it like an epic poem. Modern. Rhythmic. Direct. I studied Kate Tempest. And wrote until it felt right. It now feels like a glorious mix of all these things, and more. Is it an opera? A musical on drugs? I don’t know. But I hope that, like Günter Grass’s extraordinary novel, it rather beautifully defies description.

At the end of Dead Dog in a Suitcase (& other love songs), we left our version of Macheath raging at the world as it slipped into oblivion. Here, we start with Oskar howling mad, and observe him as he survives various apocalypses, and slowly finds a kind of balance with the insane world he exists in. His is a rite of passage, and in all the bombast and bomb-blast, he does manage to reach an understanding – that the most powerful thing he can do right now is not shout about the size of one’s destructive arsenal, but to listen. This might bring negotiation and acquiescence and perhaps even (dare I say?) humility, but it also brings him a strange sense of hope. He embraces not the over-simplified “us and them” of The Order (our Right Wing tsunami), but life in all of its fragility and complexity. Viva la complexity!

Lastly, here’s to the extraordinary Günter Grass, who died whilst we were developing this. His masterpiece is often deemed surreal, grotesque, bizarre – but, more importantly, it is wildly and sublimely human. And though some liberties have predictably been taken, I hope you find his spirit of anarchy, absurdity, rage, wit, love and humanity intact throughout.